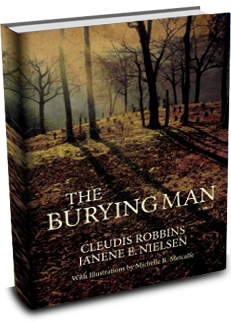

The authors have made available excerpts from the novel for you to read.

Excerpt from Chapter 1

My daddy always said that death is just like opening a door—but it ain’t, you know. Death is more like a curtain that gets finer and finer until suddenly, with your last breath, you realize that Heaven is all around you and it always has been. I wish folks could know that and be comforted by it. My daddy is grieving something fierce thinking I’m on the other side of that thick door that closed quietly, forever. I sit beside him and stroke his hair and shush his crying. “There, there now,” I say, over and over. Sometimes I think he hears me cause he’ll get real quiet like he’s listening hard at something. My mama says he can’t hear us at all but sometimes he can feel us like a warm place in a cold room.

I guess the best part of dying is seeing my mama again. She breathed her last bringing me into this world. She told Daddy she wanted me to be called Rose, but Daddy always called me Buddy—and later Bud—in remembrance of Mama being called home in the bud of her youth. Daddy talks right pretty like that sometimes. He took Mama’s passing real hard. I guess the door to Heaven seemed closed tight to him then. I was a good three years old before Daddy paid me any mind whatsoever.

My earliest memory is the sound of my daddy’s voice, a low rumble keeping company with the slow creak of his worn out steps on tired old floor boards. I guess nearly every sermon he ever preached was conceived on our peeling front porch. My daddy is probably the most famous funeralizing preacher in Harlan County, Kentucky, maybe even in all the Cumberlands. How he came to speak comfort to others when he’s never really found it for himself is one of life’s mysteries. You may have heard of him—the Reverend Oakley Grace—but folks just call him “Mournful.” It fits him somehow though it puzzled him at first. Cheerful by nature, it sat uncomfortably upon him like someone else’s smelly old coat. Funny thing is, he couldn’t remember when the coat became his and the smell too for that matter. It just did. Shoot, even I called him Mournful. It just seemed more respectful somehow. A lot of men, the good and the bad, get called Daddy one way or another, but there is, and ever will be, only one Mournful.

There’s some that say Mournful was born with the call to preach. “The seventh son of a seventh sone has the Lord’s hand upon him,” so say them that know about these things. Such men are given to visions, the power to heal, to warn and to preach. Some say just the spit of a seventh son can cure the most hopeless case. Mournful himself was less certain. There is only one thing he knew for sure: he would not spend his allotment of days digging his own grave in a Kentucky coal mine. The son of a coal miner, he learned to pray listening to his mother wrestling with the Lord to bring his daddy home each night. Every goodbye was their last and a knock on the door was a thing of dread, certain news a cave-in was upon them.

To say he was poor is dressing it up a little. ‘Bout the only thing he had was the love of his family and, most times, that was enough to get by on. Born in the Emerita Coal Mine Camp in a dilapidated clapboard house without water or light or just about anything else, Mournful spent his young days roaming the Cumberland Mountains. The storied woods and singing streams became his church. Each morning he left the valley’s shadow to be baptized anew in the sunlight of the ridge. Truth be told, he could have lived out his days in complete happiness feeling the squish of mud between his toes in the cool waters of Crier Creek hunting for minnows and crawdads and the like. With one of his mama’s mason jars in hand he was doing just that when the first remarkable thing of his life occurred.

Excerpt from Chapter 13

As Mournful rounded the bend, he could see the old black walnut tree across the road from the Denny place had fallen in the storm. Everyone knows it is the worst of bad luck for a black walnut tree to fall, no matter the reason. The ground where a

black walnut once stood is poisoned earth. Nothing can grow and everything within reach of its roots or shade has the mark of death upon them—even long after all evidence of the tree ever being there is gone. Some say it’s the devil’s own tree and shades the hidden entrances to hell itself.

While Mournful surveyed its corpse, the uneasiness of the night returned. If the sheriff’s men were willing to kill to protect the coal operators, Mournful could see no path for a peaceful solution. The storm’s debris was everywhere. More than trees had fallen in the night. The men were going to have to stand together to protect their wives and their children, their jobs and their homes. It was a fight as old as time. Mournful says the names of wars always change but the reasons for fighting them stay the same.

Excerpt from Chapter 21

Night in the Cumberlands is always hungry, swallowing everything in its blackness. Opening the back door, we pressed our eyes up against the darkness. Amid the cries of night birds, yowls of bobcats and occasional gunshots, a racking cough could be heard from somewheres out in the yard. Feeling our way back yonder, shouldering through the shadows, following the wheeze, our toes discovered a sudden nothingness—which the light of a Lucky Strike proved to be a hole, three feet wide and half again as long. At the bottom, resting on a pile of blankets with a pillow at her head was Grandma Cora. It was hard to tell who was more surprised to see the other. It took all our doing to coax Granny up out of that hole and inside the house.

How come she came to be laying in a pit in her back yard takes some telling. Ever since Grandpa Charlie died Cora had become increasingly peculiar. We had long acknowledged and accepted her fear of ever leaving her house, but of late that handicap was coupled with a fierce pride of independence. Cora just couldn’t stand the thought of anyone doing anything for her. She figured she had taken care of herself just fine, thank you, all her life and would continue to do so, living on the jars of fruits and vegetables stored in her root cellar til the day she died.

But it was the dying part that preyed on her mind. She wasn’t afraid of dying, mind you, but she couldn’t bear the thought of being beholden to someone else to arrange for her mortal remains. Not being able to take care of this final step herself gnawed at her to no end until she finally lit upon an idea—she would dig her own grave! That way when she passed on at least that much she would have done for herself.

Now this was no small undertaking, if you will forgive the pun, for a woman of Cora’s age.

She had no tools at hand to speak of, settling in the end on a soup spoon from the kitchen. Needless to say, this was slow going. The soil in Emerita is rocky and unforgiving. But the remains of a summer garden meant the first few feet was soil used to being turned. ’Sides, Cora figured she had time to dig; there were still plenty of green beans and apples in her cellar. When those were gone, she figured she would be too. Despite a number of setbacks due to rain and a less than helpful stray dog, it had really only taken Grandma four months to dig her own grave. It was one of the few pleasures of her life to look out yonder and see her handiwork and know, even in this last thing, she didn’t need anyone. She could take care of herself.

Not only that, during the excavation she had uncovered further means to help her do so. Not more than a foot down wrapped in an oil cloth, newspaper, and a couple of old burlap sacks was a sawed-off double-barrel shotgun. She hadn’t seen that gun since before her husband Charlie had died in the cave-in. She had stopped wondering where it was ten years ago. It had belonged to his father and when Charlie was eleven years old, his daddy let him shoot it. The gun knocked him down and bloodied his mouth. After that incident, his daddy called the gun “Little Charlie.” Grandpa Charlie had buried the gun after a scrape with the law, something we don’t talk about, and there it had remained all these years.

It took some cleaning and oiling but Grandma figured it still worked just fine. Having Little Charlie at her side took away some of the fears that tend to prey on widows in the night. She figured she could give as good as she got in a fight now—maybe better. Many a night she sat by her window just short of praying that some ne’er-do-well would wander up into her yard and get in her business, giving her cause to test it out.

However, the satisfaction of having dug her own grave and even of having Little Charlie by her side began to wane as a new concern came upon her. She was now consumed with the mortifying thought of dying in her house and being found by someone who would then have to steward her body to its final resting place, even if it were only out back in a ready dug hole. That’s when the final solution to her dilemma came to her. She figured she would most likely die in her sleep. She hoped so anyway. Therefore, while the good weather lasted she intended to sleep in her grave at night. That way all anyone would have to do is throw some dirt in after her. And if we had a rainy autumn, maybe the earthen walls themselves would collapse around her, her final triumph of independence. Each night when she descended a makeshift ladder, she prayed to the God she still believed in that it might be so.